We were all refugees once...

During the High Holy Days, we often are reminded of the term tzedek (justice). These is a Jewish value that many of us practice, or at least try to practice. Many of us give financially to organizations that we believe are making a positive impact on the world. Some of us serve on boards to help those organizations make important decisions. A few of us even get out from behind our busy schedules and go out to volunteer with an organization.

In Leviticus 19:9-10 we are taught to care for the stranger and the poor. God says:

“When you harvest the crops of your land, you shall not harvest all the way to the edges of your field, or gather the gleanings of your crops. You shall not pick your vineyard bare, or gather the fallen fruit of your vineyard; you shall leave them for the poor and the stranger: I the LORD am your God.”

In Mishna, Peah Chapter 8, the rabbis specify how much of the farmers’ extra crops are to be left for the poor. They are told exactly how and when different crops need to be left. Why do they do they have such specific rules? Because in the time that these rabbis existed, they believed that God owned everything, and therefore the crops did not even belong to the farmer until the farmer shared the specific portion which God had set aside for the poor and the stranger.

In this chapter we learn a number of different ways farmers are directed to share with the poor. After harvesting their portion of the crop, they are to donate a percentage of their own lot to the poor. In the end, the poor people are supposed to have enough food to feed themselves, and to be able to sell some. The rabbis believed that God wanted to give the poor people an opportunity to make money and build a life of their own. This world that the rabbis existed in had a very important message about how we are responsible for one another as human beings.

We often talk today about the words from Leviticus, v'ahavta l'reacha kamocha, (love the stranger as yourself). It goes on to remind us that we were all strangers in the land of Egypt. Therefore, our actions today, should reflect what we have learned in our history.

This year, when more than 2000 children were separated from their parents, our movement stood up and spoke out. Along with 25 other Jewish organizations, the Union for Reform Judaism signed a letter addressed to the attorney general and the secretary of homeland security that in it included the following:

“As Jews, we understand the plight of being an immigrant fleeing violence and oppression. We believe that the United States is a nation of immigrants and how we treat the stranger reflects on the moral values and ideals of this nation.”

It went on to say: “Our Jewish faith demands of us concern for the stranger in our midst. Our own people’s history as “strangers” reminds us of the many struggles faced by immigrants today and compels our commitment to an immigration system in this country that is compassionate and just.”

In June, Rabbi Jill Jacobs, along with ten other rabbis went to the border in Texas to meet some of the refugees and hear their stories. In an article Rabbi Jacobs wrote for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, she references three specific families that she met with.

Each family included one parent and one or two young children. One mother and two fathers, all who were forced to leave part of their family behind to try to find safety, in hopes that they would bring the rest of their family later on.

The three families had fled violence and gang violence in their home countries in the hopes of establishing safe and stable lives for their children. They had endured month long journeys — by bus, taxi and foot — plagued by robbery and intimidation by smugglers and others. The father from Honduras told her that he had heard news of the family separation policy while still in Mexico, but believed he had no choice but to keep heading north.

In 2006, a friend of mine, Rabbi Don Goor wrote:

"As Jews we have two options – we can relate to public policy issues from the outside in - as theory, worrying about problems on a mega scale. Martin Buber, the great theologian would call this an I-It relationship – a relationship based upon transactional value. Or, as Jews, we can relate to public policy issues from a human perspective, concerning ourselves with people, with values. Martin Buber called these I-Thou relationships – relationships infused with holiness.

At first glance the question of immigration is an I-It question – a transactional question – what is best for our economy? What is best for our jobs? However, Torah is clear – when we look at public policy questions having to do with society, the transactional questions are secondary. Torah minces no words – the human level is the crucial level, the first level, the holy level.

So, we have a choice – I-It or I-Thou?"

The words he spoke over a decade ago still ring true today. The commandment to love the stranger is the most repeated commandment in the entire Torah; even more than the commandment to love God. Torah is still clear that our treatment of the stranger is essential. That our actions should reflect our memory, that we too were strangers once. As Jews must engage in dialogue about the treatment of our neighbors, near and far.

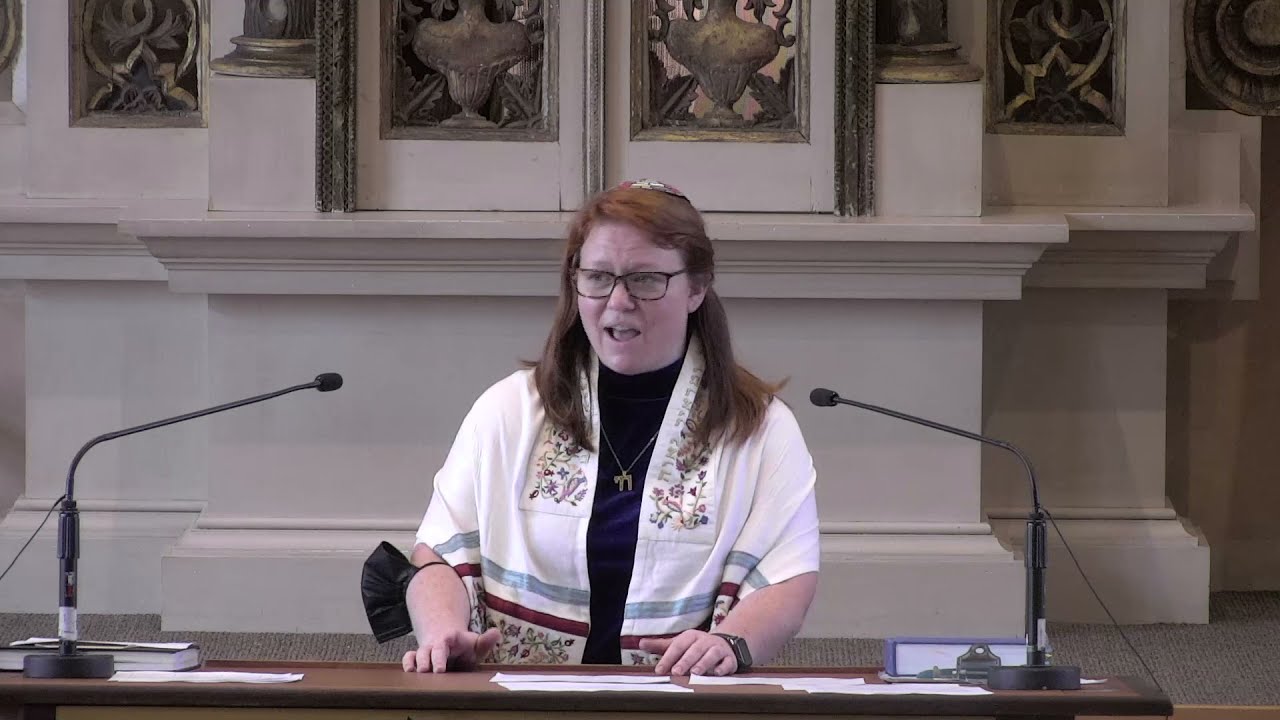

Here in Petoskey, you encounter new people on a regular basis. Welcoming the stranger into your city, into this synagogue, is already part of your personal practice. Each year or so, you welcome a new student rabbi, like myself, onto your beemah. You take the time and energy to help shape us and guide us to be rabbis who will be able to lead future generations of Jewish people. You are experts at welcoming the stranger.

I encourage you to remember this expertise that you harness when you consider public policy questions concerning society. As modern Jews, it is our responsibility to help shape our world through love and justice.

Tzedek, Tzedek Nirdof. Justice, Justice shall we pursue.

**Erev Rosh Hashanah 2018/5779