Survivors of Domestic Abuse in Torah and Today

In Eliza’s Haftarah portion, we heard the scene from Hosea which has been lifted up throughout generations of Jewish tradition. We recite this illustrious, cosmic language of the union between Hosea and Gomer, God and the people of Israel, at weddings and when wrapping tefillin. At weddings it is used as the blessing of betrothal - a promise to keep the covenant of marriage. When wrapping tefillin the verse is cited as a declaration to Adonai -- “I betroth you to me forever. I betroth you to me in righteousness, justice, lovingkindness, and mercy.” It sounds nice right… but the problem is, we tend to leave out the difficult part of the story which precedes it. We have taken the good parts and silenced the violent, uncomfortable truth of Gomer’s story. Together this morning, we are going to face some of the difficult realities about the abuse of women in biblical and contemporary societies.

In July of 2020, Pinar Gultekin, a 27 year old Turkish woman went missing and was later found dead, her body burned so badly that the medical examiners could not determine the official cause of death. Pinar had unknowingly entered into a relationship with a married man. When she learned that he had a wife, she called things off. Soon after, that married man attempted to rekindle his relationship with Pinar. When she refused and threatened to tell his wife he became enraged, murdered her, and burned her body.

Pinar was the 50th woman murdered in Turkey last year, that we know of. In 2019, 474 Turkish women were murdered, mostly by partners and relatives. The black and white photo - #ChallengeAccepted campaign that spread globally, was started by women's rights activists in Turkey to raise awareness, and to pressure the Turkish government to take action against femicide, the murder of women, simply because they are women. Black and white photos were chosen, because that is how women’s faces appear in newspapers following their murders. By posting a black and white photo of themselves on social media, Turkish women were making the statement -- that they could be next.

Gender based violence has occurred all throughout human existence. In this week’s Haftarah, we read about gender based violence in the story of the prophet Hosea. While it is not typical to read such a large portion of text, I believe it is important for us to hear it...The story is, in my opinion, one of the most difficult we face in tankah.

God instructs Hosea to marry a prostitute and have children with her. He marries a woman, Gomer; they have three children. At God’s instruction, they name their first son Jezreel -- to symbolize that later, God will break the people of Israel in the valley of Jezreel. They name their daughter Lo-ruchamah meaning ‘show no compassion’, for God will not accept the people of Israel or pardon them for their sins. They named their second son Lo-ammi, for Adonai said “you are not my people, and I will not be your God.”

Sometime later, God spoke to the children of Gomer and said:

Rebuke your mother, punish her. For she is not my wife, and I am not her husband. Remove her harlotry from her face, and adultery from between her breasts. I will strip her naked and leave her like the day she was born. I will make her like the dry desert land of the wilderness, and she will die of thirst. I will not show her children compassion, for they are children of prostitution. Their mother is a harlot who conceived shamefully.--- She said, “Let me go after my lovers who give me bread and water, wool and flax, oil and drink.” -- So, I will create obstacles in her path, I will build up a wall, and she will not find her way. She will pursue her lovers but she will not secure them. She will seek them, but she will not find them. --- Then she will say, “I will go and return to my first husband, for I was better off then than I am now.”

Then Adonai proclaimed:

She did not consider that it was I who gave her the grain and the wine and the oil, I provided the gold and silver to her -- which they used to make a false idol. Thus I will take back my grain in its time, and my wine in its season, and I will snatch my wool and linen that covered her nakedness. I will uncover her and shame her in front of her lovers, and no man can save her from Me. I will put an end to all her joy, her festivals, her new moons, and her sabbaths. I will ravage her vines and her fig trees, which she thought were wages from her lovers. I will turn her fields into brush and beasts will devour them. I will punish her for the days that she brought her offerings of worship to false idols; when she was adorned with her earrings and jewels, and she would go after her lovers, and forget me.

Following this violent scene, God offers Gomer (and metaphorically, the people of Israel) redemption. Her crops are returned to her - and her covenant with her husband is restored. As long as she remains faithful from this point forward, she will be protected and blessed.

This scene of redemption and restoration is not enough to drown out the torment that precedes it, and yet it tends to be the only part of the story we discuss.

Many commentators will claim that this story serves as a metaphor against idol worship. While the text appears to be talking about Hosea and his adulterous wife, it is actually intended as a warning to the people of Israel. In this case, God is the husband and the people of Israel are the wife. When the people of Israel sin against God by worshiping and making offerings to idols, God becomes angry and retaliates against the people.

But do we really want to put ourselves in the position of Gomer? Are we willing to subject ourselves to such a violent potential outcome?

Cheryl Exum, a feminist biblical scholar, notes that this text is one of the most problematic Biblical texts displaying violence against women -- because it portrays a male God perpetrating sexual violence against Gomer. She notes that we as readers, both male and female, are expected to sympathize with God’s perspective. This is particularly difficult for women to do, as we are much more likely to identify with the female character of the story. When the woman chooses to control her own body, and pursue other lovers to make a living, she is repaid with violence and humiliation. Exum notes that in this text “physical abuse is God’s way of reasserting his control over the woman. The prophets encourage the sinful women to seek forgiveness from her abusive husband, a message that suggests abuse can be instructional, and can lead to reconciliation.” In this story, “the divine husband’s superiority over his nation-wife lends legitimacy to the human husband's superiority over his human wife.

Stories like that of Hosea and his “sinful” wife give undue power to men over women. Both Christians and Jews must struggle with this text as a part of a shared canon. Stories of femicide and violence against women, like the story of the Turkish woman Pinar, exist in all corners of our earth. The trend of violence against those who identify as women is still far too common today.

So why then, do we continue to read this portion year after year? In Mishnah, Pirkei Avot we read the words of Hillel’s disciple, Ben Bag Bag. Regarding the purpose of studying and re-studying the Tanakh throughout our lives he teaches us to turn it over, and over, again and again, for everything can be found in Torah. He instructs us to look into it, and become gray and old with it; to not move away from it, for the Torah is our greatest resource. We are instructed by our great sages not to abandon the text when it strikes us as problematic, or no longer of use, for there is always something new that can be gleaned.

Maybe we are meant to read this story each year through our contemporary understanding of the world, as a reminder that we must protect women in our community…

Feminist biblical scholars like Cheryl Exum offer a few different approaches to studying this text. She suggests that one option -- is to respond ethically to these texts as modern day readers -- by acknowledging what we are reading, and doing something about it. Another choice she offers is to search for a competing discourse. To look for places in the text where the woman’s voice is silenced by the patriarchal constraints of a book written by men, for men, about a male deity. Finally she recommends a deconstructive reading of the text through questioning. For example, she brings in the words of professor Yvonne Sherwood who asks - “If Hosea is such a good husband and provider, why would Gomer seek another for food and clothing?”

We might ask: What was Gomer’s reaction to this? Did she know that Hosea married her because he was instructed by God? What was her reaction to being forced to name her daughter “show no compassion,” and her son “you are not my people?” How did she feel when God threatened “to strip her naked and let her die of thirst?” What might she have said when God claimed she would “return to her first husband because she had been better off with him?” Is this true, did she want to return? What did she have to do in order to simply survive?

Why is she not given the opportunity to respond and defend herself? And, after such violent treatment, why should she return to that relationship? Did she ever even have a choice?

The questions we ask ourselves about the violence in this Haftarah are similar to questions that we hear regarding domestic violence in our own communities.

In the 2020-2021 National Needs Assessment of Domestic Abuse in the Jewish Community, a study published a few weeks ago -- Meredith Jacobs, the CEO of Jewish Women International wrote the following: “COVID-19 lifted the curtains that allowed us to hide the realities of our world that were too hard to face. As we sought sanctuary through mandated quarantines, protecting ourselves from the virus that lurked outside our homes, stories began to emerge of women locked down with their abusers. The added stressors of the pandemic ramped up the violence they had already been experiencing — unhealthy relationships became toxic; toxic relationships became violent; violent relationships became deadly. When opportunities to leave home like going to work, or simply walking a child to the school bus were taken away, so too were opportunities for these women to seek help. With job loss came further financial constraints to the possibility of leaving. Some survivors shared that they hoped to contract the virus as thoughts of being sent to the hospital became the only means of escape.”

The study notes that we often place a higher value on the ‘macher,’ the donor, the well-connected-- than on the survivor. Similar to the case of Gomer in our Haftarah, we still ask ‘why doesn’t she leave?’ without recognizing that she has nowhere to go.

Our communities lack the sufficient support systems that survivors of gender based violence need in order to escape their abusers. Survivors fear leaving for a variety of reasons, including “lack of financial resources, concerns about child custody, fear of leaving the relationship, family pressure to stay with the partner, feelings of embarrassment or guilt, and a lack of support from clergy and community.”

Instead of blaming survivors for returning to their abusers, we must create a space in our community where they are both safe and supported. According to the study, victims are far more likely to seek help from their community - if the leaders of said community have previously spoken out about domestic abuse. Talmud teaches - when someone destroys a life, it is as if they have destroyed the entire world, but when someone sustains a life, it is as if they have sustained the entire world.

Every survivor has a different story and a different set of needs regarding shelter, financial, and legal support, but there is one thing they always have in common - survivors need us, especially those of us who serve as community leaders, to help sustain them and to listen to their stories. As a community, we need to equip ourselves with the knowledge and resources to help them understand their experience and validate their feelings. They need us to be able to provide options for responding to and escaping the abuse-- and to create space within our community for physical, emotional, and spiritual healing and safety.

While we can not go back and rewrite Gomer's story, we can mark it as a reminder to be better and to do more than our ancestors who stood idly by during this violent and humiliating scene. It is on all of us to make sure that our communities are safe spaces for those who suffer from physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. Maybe this story will serve as a lesson to listen to women, to believe women, to protect women, and all who suffer abuse.

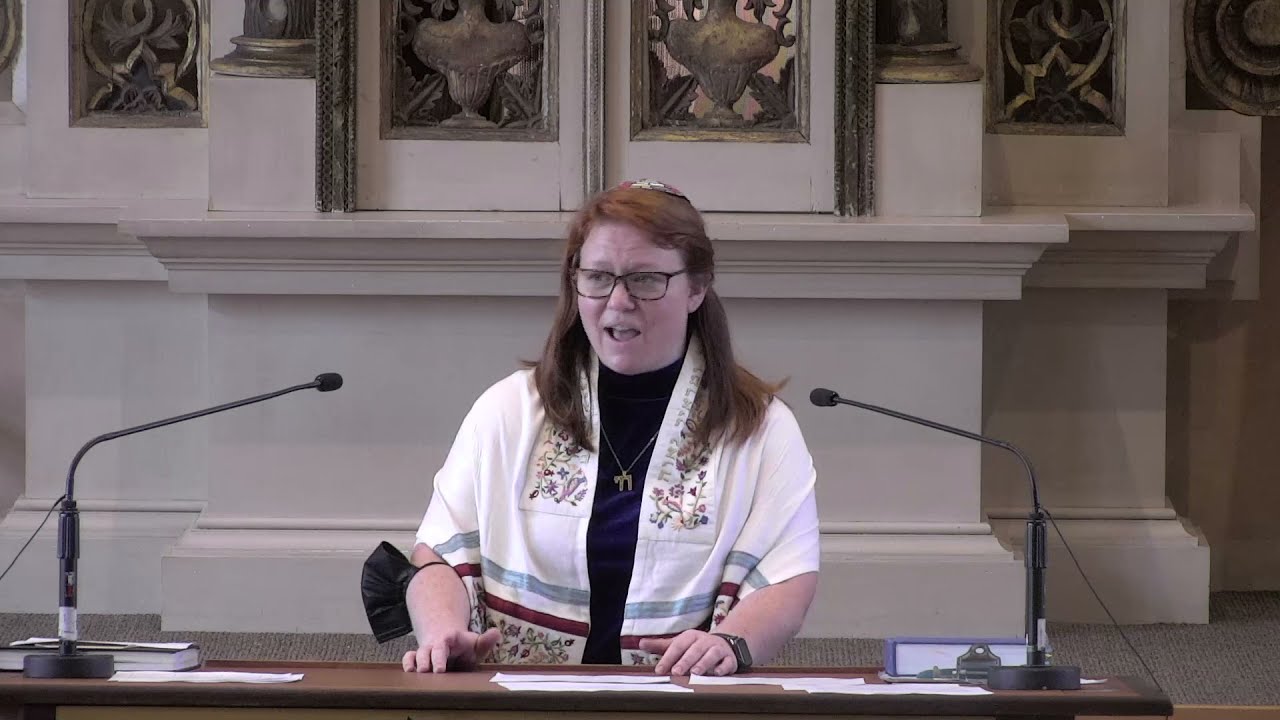

Delivered on Shabbat, May 15, 2021

Sources:

https://www.jwi.org/national-center#jewish-dv-research -- 2020-2021 National Needs Assessment of Domestic Abuse in the Jewish Community Exum, Cheryl. "Plotted, Shot, and Painted: Cultural Representations of Biblical Women"

Comentarios